There is a recurrent question making the rounds in Brussels : is Fascism returning to Italy? The electoral victory of Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia is bringing back memories from the past. While there are some similarities with 1922 and the coming to power of Benito Mussolini, there are also crucial differences.

Fratelli d’Italia is regularly described as a fascist or post-fascist party. Observers point out that the party’s symbol is similar to the one chosen by the Partito Nazional Fascista (PNF) and that Ms Meloni’s personal experience as a young woman in Rome’s popular neighbourhood of Garbatella is rooted in the extreme right.

It is true that, contrary to Germany, Italy never really came to terms with its most recent history. The WWII ended with a bloody civil war between fascists and partisans, but in 1946 the Communist leader and Justice Minister Palmiro Togliatti opted for a generalised amnesty.

Above all, many policy choices decided during the fascist regime–starting from the creation of professional orders and the nationalisation of important industrial companies–remained in place. Over the decades, a small fascist party remained a permanent feature of Italian politics.

This said, Mr. Mussolini came to power following a world war. He was elected at a time when the alternative was Soviet communism. The country was in the midst of a deep economic crisis, with intense social conflict (the so-called biennio rosso). Armed workers were occupying factories while political leaders on the left were calling for a 1917-type revolution.

Today’s Italy is in dire straits–with high youth unemployment and fragile growth—but it is not in the same situation as in the 1920s.

This said, there is a simmering similarity. Fratelli d’Italia has attracted voters frustrated by the inability of recent governments to tackle the country’s deep-seated issues. Many Italians voted for Ms Meloni as a reaction to the current establishment, which is seen, rightly or wrongly, as enriching itself at the expense of the rest of the population.

In this sense, there is a parallel with 1922, when voters opted for the PNF as a bastion against Communism, but also in a show of hands against the establishment which had governed Italy since the country’s birth in 1861 and which was represented by the likes of Francesco Crispi and Giovanni Giolitti. If Ms Meloni was successful in attracting voters from the rich North of the country, it’s because many entrepreneurs hope she will be able to cut taxes and reduce bureaucracy. They voted more by opportunism than by ideology.

More generally, by appealing to principles such as Family, Motherland and God, reminiscent of Mr Mussolini’s slogans, Ms Meloni is winking to a small minority of Italian society which over recent decades has become as secular as in many other European countries.

Therefore, her links to Fascist ideology are limited, aside from her desire to make the State a stronger actor in the economy – a goal that will require her to come to terms with an overblown public debt as well as the EU budget and competition rules.

The new government’s policies will much depend on the balance of power between the three rightist parties: in addition to Fratelli d’Italia, the Lega and Forza Italia. While Ms Meloni appears to be aiming for a pragmatic approach on economic matters, as she well knows that rattling markets would endanger her future at the helm of the country, she might follow the Hungarian line, by disrupting the functioning of the EU whenever useful for domestic purposes.

After all, she has argued against the primacy of EU law over national law in line with other controversial leaders such as Viktor Orbán and Mateusz Morawiecki.

Alliances between member states depend on evolving interests. They are not written in stone. This said, following the Italian elections, the weak element of today’s European institutional framework is the EU Council. Poland and Hungary together with their new ally Italy are close to mustering a blocking minority – they represent 24% of the EU population vs the 35% needed to block the functioning of the body grouping the member states.

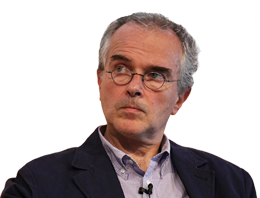

(In the picture above, Giorgia Meloni, 55, leader of Fratelli d’Italia)