By Beda Romano – BRUSSELS – On Sunday March 24 at 9AM, Nicos Anastasiades, the president of Cyprus, boarded a special aircraft of the Belgian Air Force sent in haste to Nicosia by the President of the European Council Herman Van Rompuy. The plane had landed at dawn. "We wanted to be sure to have him here in Brussels at midday, before the start of the Eurogroup", says a leading figure in the negotiations that on Sunday night, exactly a week ago, led to a long-fought agreement between Cyprus and its international creditors.

The

10 days that shook the euro area, from March 15 to March 25, have been marked

by long meetings; impromptu conference calls; blunders and misunderstandings,

tensions, fears, controversial decisions, some of which have been reneged on,

while others are now considered a model for the future; and last-minute choices

like the one that prompted Van Rompuy to send an air force plane to pick up the

Cypriot president. “I would not be at all

surprised if the Cyprus week-long episode does not register in history’s annals

as a major turning point; as the moment in history when Europe moved beyond the

pale”,

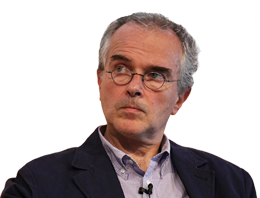

says the Greek economist and Athens university professor, Yanis Varoufakis.

An account of the events of the last 10 days leaves the impression that the

Cypriot crisis is far from over. Will the country restructure its banks and

remain a member of the European Union? Will the restrictions on the movement of

capital decided in Nicosia extend to other countries? More generally, the

negotiations over the last two weeks have shown Van Rompuy’s negotiating

ability, the personal limits of the new Eurogroup president Jeroen

Dijsselbloem, and the surprising helplessness of the finance ministers, overwhelmed

by agreements which have become increasingly complex from a technical point of

view. The arrival of Anastasiades in Brussels, on Sunday March 24, was preceded

by a chaotic week.

Following his election in February, the new Cypriot President decided from the

start to negotiate an aid package with the Troika – the European Central Bank,

the International Monetary Fund and the European Commission. A round of

negotiations between the sherpas took place. Concerned about a situation that

was dangerously systemic, Dijsselbloem decided to convene an emergency meeting

of the euro area Finance Ministers on March 15, in the wake of the European

Council of heads of state and government which was scheduled to end that same

afternoon.

The meeting started in the evening, but as it started it was clear that it

would last through the night. At a technical level, diplomats had not been able

to solve a number of hurdles. The IMF raised the issue of debt sustainability

in Cyprus, as it had done in the past with Greece. It requested and obtained a

contribution from the private sector as a pre-condition to allow for

international loans. Taxing bank accounts became an option, but the

Anastasiades administration was torn between the desire to protect Cypriot

citizens and the instinct to preserve Russian investors. The discussion lasted

for hours. Finally, a compromise emerged at dawn: it was based on taxing

deposits below 100,000 euros at a 6.5% rate and all other deposits above this

level at a 9.9% rate.

To avoid confusion in communication, Dijsselbloem asked his colleagues to be

the only minister to hold a press conference at 4 in the morning: "All the

ministers agreed – recalls a diplomat -. However, the president of the

Eurogroup did not speak out on the

burning question of taxing depositors. We were all taken aback." Within a

few hours, the newly-announced measures created doubts and resentments. In

Cyprus, the compulsory levy sparked new protests. Most critics pointed out that

the choice of taxing bank accounts ran against the promise to guarantee all

deposits under 100,000 euros. Another official said: "They reckoned

without one’s host, finding an agreement which was too technical and not

political enough."

Two days later, the Cypriot Parliament roundly rejected the compromise reached

in Brussels by Cypriot Finance Minister Michalis Sarris. In the wake of the

vote in Nicosia, the Eurogroup was forced to convene another emergency meeting,

this time by teleconference. In between the lines of a statement issued

thereafter, the finance ministers admitted they had made a mistake and

supported the Cypriot attempt to find a more balanced solution. A European

negotiator says: "In that circumstance, the most serious consequence was

to sabotage the Anastasiades government, which had just been elected with a

pro-European agenda. What an awful impact on the image of Europe."

Officially, the ball was in the Cypriot camp, but several prominent

members of the European establishment admitted they had no trust in the

Cypriot government: was the country at the mercy of events or just looking for

byzantine solutions? As for the

Cypriots, they have lived for 500 years under the rule of the Venetians, the

Ottomans, and the British. Their entry into the European Union in 2004 was a way

to free themselves from the surrounding regional powers, but now they saw the

EU as a new dominating force, with which to play hide and seek. On

Thursday March 21, the ECB decided to harden the tone: it warned that it would

stop extraordinary liquidity injections into Cypriot banks in the absence of an

agreement.

While in Brussels, at a hearing in the European Parliament, Dijsselbloem under

fire took "full responsibility" for the latest decisions of the

Eurogroup. In Frankfurt the ECB wanted to force Cyprus’ hand as it attempted to

snatch help from Russia. That same Thursday, the finance ministers came

together again by teleconference. Busy in Moscow, Sarris was absent, awkwardly

replaced by the Labour Minister Haris Georgiadis. "At some point – a participant

recalls – a minister asked if there was an emergency plan in case of no bailout

agreement. No one was able to answer".

Meanwhile, in Cyprus the popular protest was mounting against the bank closures

imposed by the government to prevent capital flight. The parliament adopted two

laws on Friday March 22: the first was on the resolution of troubled banks, the

second on the restrictions on the free movement of capital. The Cypriot

government had decided to reopen the banks on Tuesday March 26. An agreement was

urgently needed, so much so that Dijsselbloem convened a new emergency

Eurogroup meeting in Brussels on Sunday, March 24. Worried about the collapse of the first

agreement, Van Rompuy decided to cancel in haste an EU-Japan summit in Tokyo

and to participate in the negotiations personally.

As the Cypriot government continued to negotiate with the Troika in Nicosia,

European Council officials in Brussels organized the arrival of Anastasiades.

"We decided to keep open as a last resort the option to convene a summit

of heads of state and government," an official explains. Meanwhile,

arriving in Brussels, ECB President Mario Draghi warned that his ultimatum

expired on Sunday at midnight, not on Monday at 6 pm, as many secretely had

hoped. Meanwhile, in Cyprus the head of the Orthodox Church, Archbishop

Chrysostomos II, came out bluntly: "It is certain that [the euro] will not last in the long term, and the

best is to think about how to escape it."

The first challenge was to find an agreement within the Troika. While the IMF

called for the closure of the two most indebted banks (the Laiki Bank and the

Bank of Cyprus), the Commission wanted to save one of the two in order to allow

it to continue to support the economy. A compromise was finally reached, but an

accord remained to be found with the Cypriot authorities. With strong links

to the island’s financial industry, Anastasiades wanted the two banks to remain

open. "The state of the Laiki Bank was outrageous. It was really

impossible for us not to impose its closure”, says a European negotiator At one

point, during the negotiations, the Cypriot president even threatened to

resign.

Late on Sunday evening, Sarris met

a number of national delegations proposing solutions that Anastasiades himself

had refused with representatives of the Troika. New byzantine procedure? A form

of friendly fire? "We were confused to say the least," a diplomat

admits. The negotiations were led by Van Rompuy and the heads of the Troika,

while the ministers were kept informed only from time to time: "In fact,

the Eurogroup was bypassed – another diplomat recalls –. It only gave a formal

endorsement to the final agreement." Many ministers spent the evening in

the offices of their national delegations, waiting, frustrated.

Suddenly, close to midnight, after yet another rumor regarding an extraordinary

European summit of heads of state and government, an agreement was found. It

included the closure of the Laiki Bank, the restructuring of the Bank of

Cyprus, and losses for both depositors and bondholders. Yet, optimism for the

future remains fragile: "The crisis is not over – says a high placed

European official –. The Cypriot economy has boomed artificially. Now we need

to bring it back to the size of the island. In addition to supporting the country,

we need to follow step by step the bank restructuring process and the

restrictions on the movement of capital. Can we trust the Cypriots?"

In Europe, there is little trust for Cyprus. In Brussels and in other capitals,

there is also the awareness that the Cypriot crisis has divided the 17 members

states of the eurozone, left indelible scars in the euro area, and weakened the

president of the Eurogroup. By declaring that the contribution of the private

sector is a new model for the management of banking crises, Dijsselbloem

created new tensions between markets and governments. "2013 will be a

decisive year for the debt crisis – a diplomat sums up –. There is the risk of

witnessing many more Munich Conferences in which all participants say they have

won, while in fact they are all losers, especially Europe."

(A shorter version of this article was published in Italian in Il Sole/24 Ore dated Mar 31 2013)